My latest article for this is tomorrow (see the published article here) – the show is on at the Wysing Arts Centre near Cambridge until November 20:

We inhabit vast natural resources. We sense everything around, under, and above you. Our research and development activities are based on a profound understanding of the biological processes in living organisms. We develop solutions to accelerate human health and evolution. – Ophiux, 2016.

Following her “Multiverse” residency at the Wysing Arts Centre in 2015, Joey Holder’s solo show, Ophiux, draws us into the possible near future of biology and medical sciences. Pulling the notion of multiverse – the unknown or infinite number of potential parallel universes – back to terrestrial grounds, Holder explores the understanding and mapping of our ecosystems and anthroposystems as well as the potentiality of global genomics.

Supported and informed by computational biologist Marco Galardini and senior biodiversity biologist Katrin Linse, Joey Holder has devised a two-part exhibition comprising an installation room as well as a video piece. Both rest on the premise of fictional pharmaceutical company Ophiux and its claim at mapping every form of life and all genomes. While stemming from reality, with real-life global projects such as Google Genomics or companies such as Illumina devising “complete workflow solutions for easier, more accessible genomic analysis”, Ophiux takes us a step ahead into a future of digitized and fully automated biology.

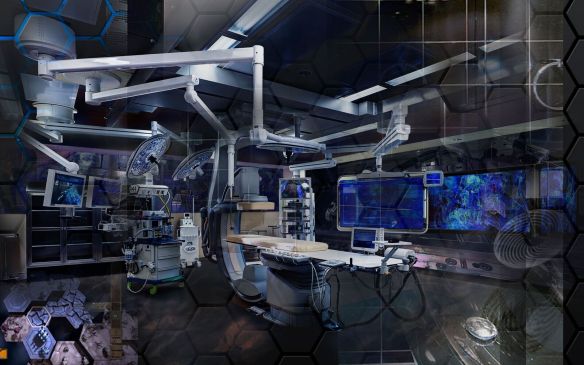

The installation room is appropriately clinical and sterile – visitors have to wear protective shoe covers to thread the immaculate white floor – boasting larger than life-sized medical machinery, futuristic looking X-ray imagery and specimen tanks with their sea-creatures. To the layperson there is a glimpse of something uncanny (in the strict sense of the word) and intimidating in this imperceptibly oversized, not entirely familiar medical environment. Viewed on its own however, the installation seems somewhat too literal and holds more meaning when visited after the show’s pièce de résistance – the film – which infuses it with the immersive power it otherwise lacks.

The film is projected in an adjacent building of the rural half-farmhouse half-white cube Arts Centre. The obscurity of the projection room lends itself perfectly to the sci-fi-ish underwater exploration the viewer is about to embark on. In what appears like the commercial trailer of this fictitious speculative pharmaceutical company, real arctic submarine footage alternates with medical imagery and computer generated images. The organic, the mechanical and the viscerally amorphous overlap to create a window onto the medical sciences of the future. In accompanying narrative subtitles, Ophiux asserts its total mapping of the marine ecosystem – presently still vastly alien and fascinatingly unknown – and how the extracted genetic data can be used to benefit human evolution and life expectancy. There is something very “Gattacian” in this systematic genomic extraction, this reduction of life to usable data and conceivable DNA manipulations; there is something eerily demiurgic in this potential power. Similarly to high-tech artists such as Stelarc, Holder raises here the philosophical (and topical) question of the increasingly fusional human-machine relationship and interdependency. We can envisage here the immense potential of technology for human preservation but are also confronted to the paradox of pursuing better and longer lives through the lifeless, the mechanical, at the risk of the latter overtaking the former and possibly supplanting human knowledge.

More speculative than critical, Joey Holder’s show is sitting somewhere in-between utopia and dystopia. It is fed by the artist’s fascination with our universe and things yet unknown and poses open-ended questions about the future of science, medicine, biology and human-machine interactions. Wherever science and technology take us Holder is not yet done with the subject and sees her experimentations continuing online (appropriately). Also a trained diving instructor, she longs once again for the life aquatic; we hope her underwater fascination and future endeavours will continue to fuel her explorations of the mysteries of life in all its forms.

– Emilie C.